Andrew Paquette Finds Cryptographic Algorithms

in the Pennsylvania State Board of

Elections Voter Registration Data Base

Article Published

by Jerome R. Corsi, Ph.D.

Andrew Paquette, Ph.D., has found an algorithm in the Pennsylvania State Board of Elections (SBOE) voter registration database. Having previously found an algorithm in Wisconsin’s SBOE voter registration database, Paquette has no discovered cryptographic formulas embedded in two of the 2020 battleground states.

Paquette has now found similar algroithms in a total of seven states: New York, Ohio, Wisconsin, Hawaii, Pennsylvania, as well as Texas and New Jersey (final reports in progress).

Paquette stressed the importance of finding these various algorithms:

A fundamental rule of database management is that all data should be transparent, traceable, and used only for its intended purpose. The algorithms found in various state databases violate this rule by introducing what amounts to undocumented attributes into the database. This makes it untraceable by normal means and can enable manipulations that violate the intended purpose of the databases.

His analysis demonstrated that algorithms are in nine of Pennsylvania’s 67 counties, including Allegheny County (that includes Pittsburgh) and Philadelphia County (that includes the city of Philadelphia):

Initial results reveal 115,434 cloned records in Pennsylvania’s current database, a number sufficient to justify ID-tracking algorithms. Nine of Pennsylvania’s 67 counties employ a complex algorithm mapping Legacy ID (LID) number to SBOE ID numbers. Notably, the counties where algorithms are present include Allegheny and Philadelphia counties, which together account for 22.45% of all registrations.

Once again, Paquette found thousands of voter records that should be removed but are still present in the SBOE voter registraton database.

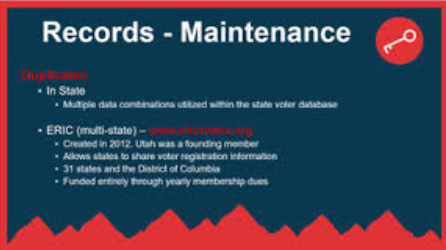

Pennsylvania’s voter database contains 8,846,634 records, of which only 9,924-19,846 (about 0.11%) are potential clones. These were identified by matching last name, first name, and date of birth – a method aligned with many state election regulations for initial duplicate checks.

While this identification method may produce some false positives, the combination of full name and complete birth date sharing is statistically rare. The most common exception involves immigrants with missing birth date information who are assigned default dates.

The number of clones in Pennsylvania, while problematic, may not alone justify the implementation of a complex voter tracking algorithm. However, this doesn’t preclude other reasons for such a system:

- There may be additional suspicious records not identified by this analysis.

- The system could be preemptively positioned for future use or expansion.

- Other administrative or operational factors unknown to outside observers might necessitate this complexity.

Analysis of Pennsylvania’s voter records revealed several anomalies:

- 26,453 registrations predate the voter’s birth

- 29,707 voters with recorded votes before their 15th birthday

- 85 cases where the last vote date precedes the birth date

These anomalies are primarily concentrated in Blair, Dauphin, and Venango counties.

Of greater concern are 228,997 active records with no activity since 1/1/2018. Pennsylvania law requires inactive status for voters after missing two successive federal elections. Since 2018, three such elections have occurred (2018, 2020, 2022), meaning these records should be inactive or removed.

These outdated active records are mainly found in:

- Philadelphia: 39,856

- Allegheny: 24,065

- Montgomery: 12,619

- Bucks: 11,170

- Delaware: 9,217

Ignoring voter status, 514,422 records show no activity since 1/1/2018. While Pennsylvania lacks a strict removal timeline, federal law allows removal after two federal elections without activity, following an unanswered confirmation notice. The persistence of these records through three election cycles raises questions about list maintenance procedures.